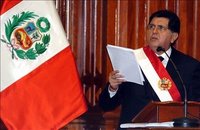

Alan García had a catastrophic presidency in the 1980s. He now has a chance to redeem himself

Alan García had a catastrophic presidency in the 1980s. He now has a chance to redeem himselfTHE last time he was sworn in as president, in 1985, Alan García spelt disaster for Peru. His government unilaterally cut payments of its foreign debt, froze prices and interest rates while raising wages and ended its five-year term with hyperinflation and an upsurge in violence by left-wing guerrillas. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) denounced his policies as reckless. On July 28th Mr García, now 57, will take the oath of office again after winning a close election against a more populist rival in June. He claims to be a wiser man. After the taming of the guerrillas, and four years of economic growth of better than 5%, Peru is in much better shape than he left it. His task now is to preserve these gains while spreading the benefits to the half of the population that lives in poverty. That will not be easy.

Early indications are that Mr García means to join Latin America's club of moderate left-leaning presidents, who fight poverty while pursuing responsible economic policies. His first post-election visit was to Brazil's president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who until now has done just that. José Antonio García Belaúnde, a career diplomat who is to be foreign minister, says his top priority is a free-trade deal with neighbouring Chile, also governed by the pragmatic left. During the campaign Mr García clashed with Venezuela's Hugo Chávez, who backed his opponent and is shunning his inauguration.

The new finance minister will be Luis Carranza, one of Peru's most orthodox economists. A former banker and deputy finance minister, Mr Carranza is likely to pursue the fiscal targets established by the outgoing government of Alejandro Toledo: a non-financial public-sector deficit of no more than 1% of GDP and real growth in spending of 3% a year or less. That will help contain inflation, which was less than 1.5% in the first half of 2006. The IMF's western-hemisphere director, Anoop Singh, praised Mr García's commitment to a “prudent economic policy”. Other multilateral lenders, such as the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank, are promising billions of dollars in fresh aid.

While continuing the economic policies of his unpopular predecessor, Mr García is trying to appear less self-indulgent. He has promised a cull of government offices, including the first lady's, and cuts in salaries of top officials, starting with his own, which will be reduced from $13,000 a month to $5,000 (Mr Toledo notoriously raised his pay upon taking office). He will dispense with the traditional inauguration ball. In all, he proposes to save $400m within six months, money that will be spent on increasing the number of water connections in Lima, the capital, and pulling the Andean region out of poverty. That ought to help Mr García's party, the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA), in local elections in November, which are already being touted as an early referendum on his government. A quarter of Lima's 8m people are without water; in the impoverished highlands, Mr García was soundly beaten by his rival, Ollanta Humala, in last month's election.

Yet Mr García has had little to say about the policies required to secure growth and reduce poverty over the long term. Judging by exam results Peru's education system is among the worst in the Spanish-speaking world, but he has proposed no plan to reform it. The health service is little better, but Mr García has not dared to defy health workers, an important part of APRA's constituency. His supporters rightly describe the tax code as a “Frankenstein creation”, but have suggested no solution. Mr García must soon decide whether to negotiate a tax increase with many big mining companies, which are earning windfall profits but are exempt from a 3% royalty under agreements signed in the 1990s.

Mr García is timid in part because his political position is shaky. A recent poll puts his approval rating at 50%, low for an incoming president. APRA has just 36 of the 120 seats in the unicameral legislature, compared with 42 for Mr Humala's Union for Peru. Mr Humala has promised fierce opposition and continued agitation for nationalisation of oil and gas, though his position will be weakened by an apparent split within his party. Mr García will respond by giving APRA a limited role in the government, leaving space for other parties (he has promised that half the cabinet jobs will go to women). Jorge del Castillo, expected to be the president's chief of staff, is a master conciliator. If the government does well in local elections, Mr García's policies may become bolder.

To an uncomfortable degree, his success depends on events outside his control. Peru owes much of its economic growth to buoyant exports—$20 billion in the year to June—which in turn are reliant on high prices for minerals, especially gold and copper, and on trade concessions from the United States. Both are vulnerable. Any downturn in commodity prices would drag down GDP growth and put the government's fiscal targets at risk. Peru's exports to the United States, a quarter of the total, are hostage to the American Congress, which is deciding whether to ratify a free-trade agreement signed by both countries (and ratified by Peru). If it does not do

so by the end of 2006 duty-free entry for some 6,000 Peruvian products could expire. American importers may already be looking for alternative suppliers. Exports to the United States rose 12% in the first half of this year, well below the 58% gain during the same period last year. A sag in exports and the economy would put Mr García's new sobriety to the test.

so by the end of 2006 duty-free entry for some 6,000 Peruvian products could expire. American importers may already be looking for alternative suppliers. Exports to the United States rose 12% in the first half of this year, well below the 58% gain during the same period last year. A sag in exports and the economy would put Mr García's new sobriety to the test.

0 comentarios:

Publicar un comentario